Search

SearchIn its most basic form, a content delivery network (CDN) is nothing more than a bunch of caching nodes.

The reason that it’s a bunch is related to:

CDNs aren’t magic, and running them is an effort that combines caching and request routing.

Here’s why people use a CDN:

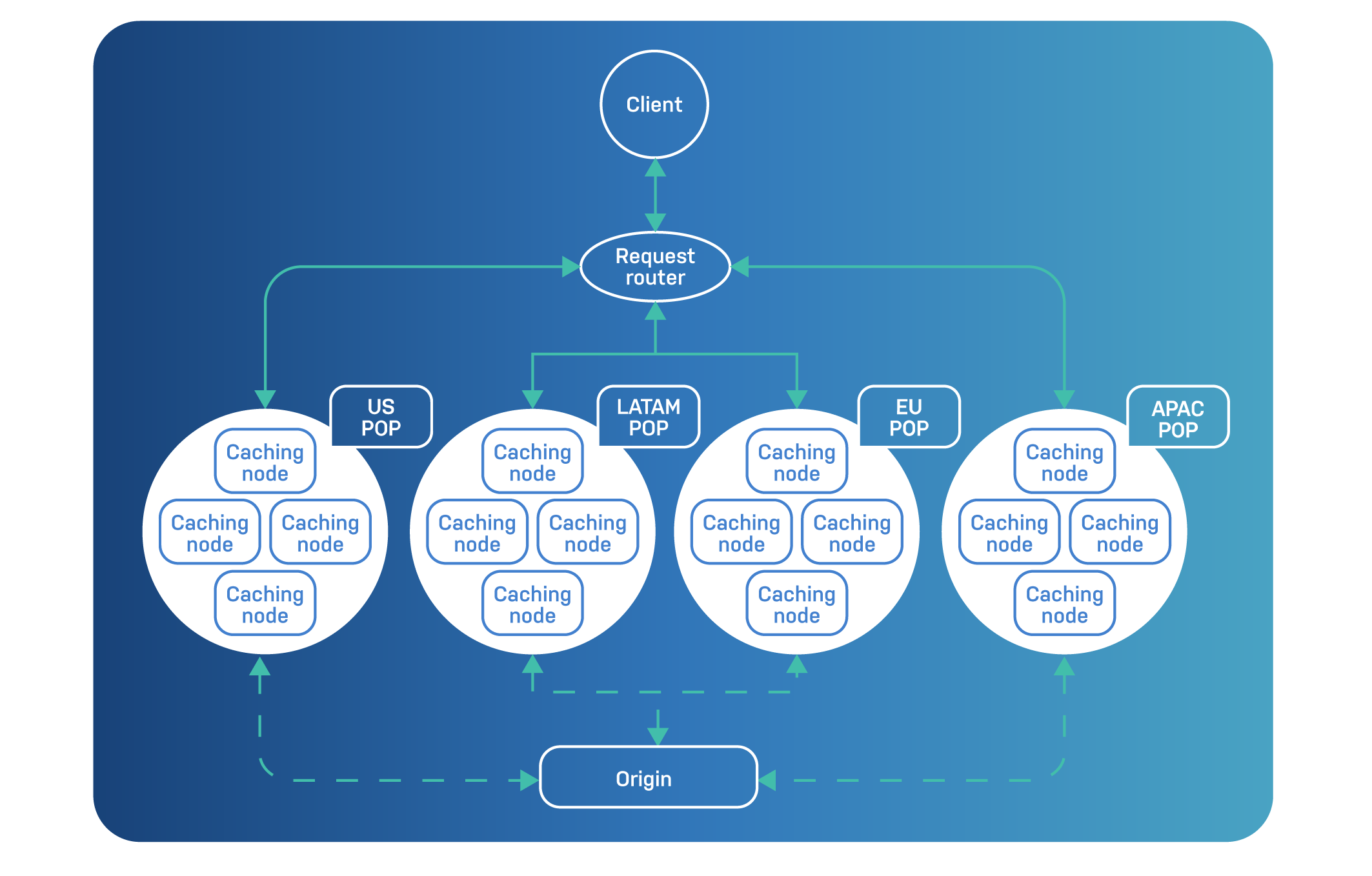

CDN providers tend to have many points of presence (PoP): these are data center sites where they host a number of caching nodes and where network connectivity is good.

These PoPs are typically spread across various geographical locations to ensure network latency is low for as many key regions as possible. Even though fiber-optic cables are enormously fast, accessing content that is thousands of miles away from the user can still result in latency.

Having global coverage ensures that any user, regardless of their geographical location, has minimal network latency. In the end, the combination of caching and networking has to result in an acceptable time to last byte for any HTTP resource that is requested.

Especially for latency-sensitive use cases like OTT video streaming, having a decent and constant throughput is crucial. And for live video, for example in a sports context, any latency seriously impacts the quality of experience.

These PoPs are mostly in key geographical areas or areas with significant demand. Here’s a simplified diagram that features four PoPs:

This CDN has four PoPs:

For the sake of simplicity, each PoP only has a handful of caching nodes. In reality, PoPs can consist of dozens or even hundreds of caching nodes.

As mentioned earlier, a CDN is nothing more than a bunch of caching nodes.

It is the caching that ensures the stability of the origin platform. But the fact that a CDN has all objects cached globally is a myth: cache storage is precious, and CDNs want to be selective about what they cache, in which nodes they want to cache, and for how long.

Quite often it’s not about the cache hits; it’s about how good your misses are.

It is unrealistic to expect that a CDN has enough caching capacity in each PoP to cache everything. There is just too much data out there: ranging from high-resolution images to 4K-quality video-on-demand catalogs.

As long as the time it takes to fetch the content from the origin is acceptable, there’s no real violation of the Quality Of Experience. And in the case of Varnish, features like content streaming and request coalescing will have a positive impact on both platform stability and Quality Of Experience.

CDNs also try to figure out how likely it is that anyone else will request the content that is being fetched from the origin. If the content appears to be long-tail content, the caching node might decide not to insert the object in cache until it is requested again.

Many CDN architectures implement multiple caching tiers, in which each tier has its own role. Some tiers are only there to cache hot data and are primarily there to route cache misses to other tiers that have more storage.

Some tiers may operate on a memory-only basis, while other tiers may combine disk storage and memory.

The caching policies of some CDN providers might be very complex, depending on their needs.

Having caching farms with good network connectivity all over the world is one thing; routing client requests to the right PoP is another.

Later in this chapter we will cover some request routing strategies in detail, but at this point we can generalize and say that potential request routing strategies are:

And quite often it’s a mix of various strategies.

The first step involves a basic localization of the client: on which continent is the client located? Does the client IP address match one of the major regions where we have PoPs?

The next step may involve network routing methodologies, such as Anycast, which announce an IP address in multiple locations and can calculate the shortest route to a PoP.

Although commercial CDN services are easy to use, and although they have the scale to cover the most significant parts of the globe, they are black boxes.

For companies that want a tighter grip on their content delivery strategy, relying solely on a CDN-as-a-service can prove to be the wrong bet.

At a certain scale, these services can also become expensive. That’s why a lot of companies are building their own CDN, or at least a selection of PoPs that fit into a hybrid CDN strategy.

For companies that serve the majority of their traffic from the same geographical region as their origin, it makes sense to build a local CDN. Telecom companies and national broadcasters fit into that category. For the latter this is usually related to OTT video streaming.

It is also possible that your CDN provider doesn’t have a PoP in an area where a lot of your users are located. This is also a reason why you would build a private CDN PoP there.

What we also see is that companies build a local CDN as an origin shield: it protects the origin from revalidation requests coming from the various PoPs of their CDN service provider. The irony is that these revalidation requests are the equivalent of a DDoS attack, which requires origin shielding.

Based on these scenarios there are actually three main reasons why companies build their own CDN:

If you already have data center capacity, networking resources and infrastructure, building your own CDN can be a very sensible thing to do.