Search

SearchAs mentioned earlier, the VCL language allows you to extend the behavior of various Varnish states that are part of the Varnish finite state machine.

This probably makes sense to some extent, but without a visual representation, it is a tough concept to grasp.

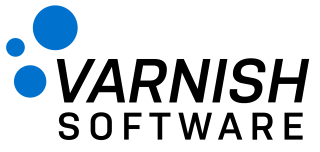

Here’s the flowchart that describes the states and the state transitions of this finite state machine. The diagram below represents the interaction between a client and Varnish.

It all starts when Varnish receives a request from a client.

vcl_recv gets called, and depending on certain request criteria, a

couple of different actions can be taken.

These actions control which path is taken through the finite state machine:

vcl_recv, vcl_hash, vcl_hit, vcl_deliver path represents

the desired outcome: a cache hit.vcl_recv, vcl_hash, vcl_miss, Backend fetch, vcl_deliver

path represents an acceptable outcome: a cache miss.vcl_recv, vcl_hash, vcl_pass, Backend fetch, vcl_deliver

path represents an undesirable outcome: bypassing the cache.vcl_recv, vcl_pipe path represents an escape plan: bypassing

HTTP entirely and switching to TCP.vcl_recv, vcl_hash, vcl_purge, vcl_synth path represents a

cache purge, which explicitly removes an object from cache.Remember: cache misses aren’t a bad thing. A miss is just a hit that didn’t happen yet.

There’s always the incoming request that triggers the start of the flow, but there must also be something that ends the transaction. In HTTP, we always expect a response to be returned.

From VCL, we can

return(abandon), which will just drop the connection. This can be desirable in some cases but breaks the HTTP transaction, and that’s another story.

And that’s how the finite state machine ends the transaction: by delivering a response to the client. It could be a cached object, it could be a backend fetch, or it could just be synthetic output.

What you don’t see in this diagram is the backend flow. When there is a cache miss, or the cache is bypassed, you’ll need to connect to the origin and fetch the result. In this diagram, backend interaction was abstracted into a single backend-fetch state.

Let’s have a look at the backend flow in some more detail.

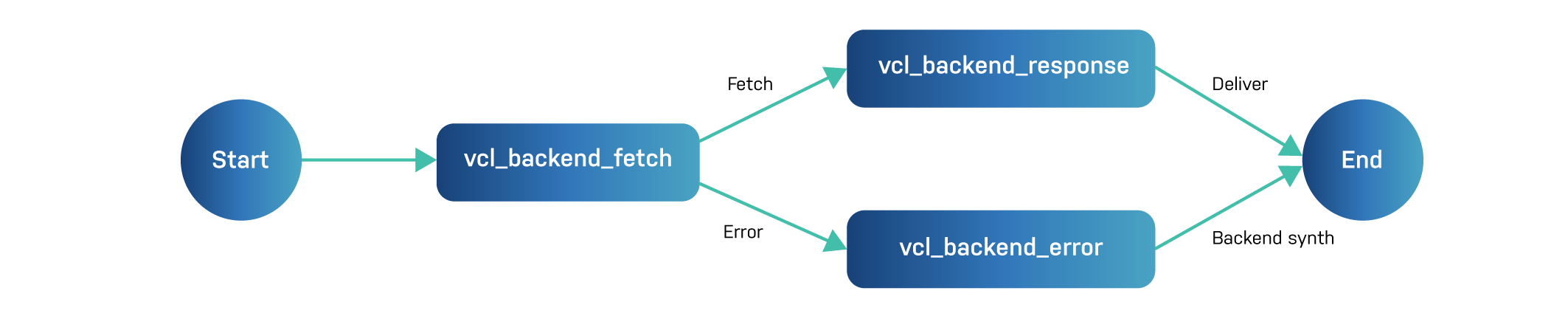

The backend flow represents the communication between Varnish and the origin server.

As you can see in the diagram below, the flow is a lot simpler compared to the client-side flow:

In vcl_backend_fetch, the request to the backend is prepared, and the

original client request is turned into a backend request.

Depending on what happens on the backend, you either end up in

vcl_backend_response when the request is successfully processed, or in

vcl_backend_error when an error occurs.

In vcl_backend_response a number of checks happen to decide whether or

not to cache the response. Eventually the response is sent back to the

client-side logic of Varnish, which will send the response to the

client.

The vcl_backend_error stage is reached when Varnish fails to connect

to a backend, when a backend is considered as sick, or when the

backend doesn’t respond in time. You can also reach this stage from

vcl_backend_fetch or vcl_backend_response by using a return(error)

statement.

The result is that a synthetic error is returned and sent back to

Varnish’s client-side logic with an HTTP 503 Service Unavailable

error.

Surprisingly, other 500-range errors that were received from the

backend aren’t considered errors. They can be cached,

vcl_backend_error is not triggered, and the response is sent to the

client without any interference from Varnish.

Whether you have a successful response, or an error, a backend response is returned, which in its turn will be sent to the client.